A Whole-Hearted Solution

A minimally-invasive implant can help patients experiencing heart failure from a lifelong defect

If you begin experiencing shortness of breath or an irregular heartbeat in your forties or fifties, you may look into your recent past to discover the problem…a lack of exercise, a change in diet, or just the simple fact of getting older. But for some patients, looking back five, ten, or even twenty years won’t uncover the cause. It happened before they were born.

“An atrial septal defect, or ASD, is a congenital defect,” explains Michael J. Babcock, MD, a board-certified interventional cardiologist who practices in The Heart Hospital at St. Joseph’s/Candler. “It is a hole in the wall of the heart that has developed in utero.”

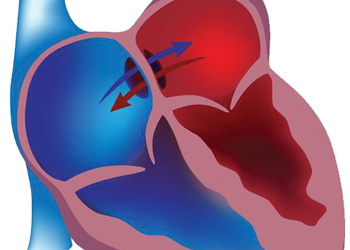

The heart has two sides, each with an upper and lower chamber. These two sides are separated by a wall called a septum. An ASD is a hole in the septum between the upper chambers. This hole allows blood to flow from the left side of the heart to the right side

Sometimes ASD is caught in very young patients by pediatric cardiologists. However, for others the symptoms won’t appear until middle age or older. It takes time, but continuous high pressure blood flowing into a low pressure system can eventually cause right-sided heart failure.

Too Much Pressure = Risk For Stroke And Other Problems

“I equate

the left side of the heart to a fire hose, with high, powerful pressure, while the right side of the heart I equate with a garden hose,” Babcock says. “With too much pressure in the wrong direction, you can actually stretch that chamber

out. If the chamber is enlarged, people can have atrial fibrillation, irregular heart rhythms, or signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure. Unless you stop the flow that is causing the enlarging, the heart failure can get worse and could eventually

be irreversible.”

“I equate

the left side of the heart to a fire hose, with high, powerful pressure, while the right side of the heart I equate with a garden hose,” Babcock says. “With too much pressure in the wrong direction, you can actually stretch that chamber

out. If the chamber is enlarged, people can have atrial fibrillation, irregular heart rhythms, or signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure. Unless you stop the flow that is causing the enlarging, the heart failure can get worse and could eventually

be irreversible.”

Patients with ASD are also at risk for stroke, because the hole could allow a blood clot to travel from the right side to the left side, where it could travel to an artery and block blood flow to the brain.

Sometimes surgical treatment is necessary for certain patients. For many years the choice for people in this region was between having open-heart surgery or traveling to cities like Atlanta for a minimally-invasive procedure involving a device called a septal occluder.

A Perfect Fit To Stop The Flow

Now Dr. Babcock, the area’s only fellowship-trained interventional structural cardiologist, can implant this device in The Heart Hospital without open-heart surgery.

The St. Jude Amplatzer Septal Occluder is a two-disc, button-shaped device that Dr. Babcock positions in the hole using a flourascope and intracardiac ultrasound.

“We bring the device through the hole, deploy one disc on the left side, pull it snug against the septum, then deploy the other disc on the right side,” Babcock explains. “Then we use transesophageal or intracardiac echocardiography to know that there’s no more blood flow through that hole, and that the device is very well seated.”

The patients that Dr. Babcock has treated with the St. Jude Amplatzer Septal Occluder have gone home the day after their surgery.

“We have found that this simple device-based closure was tremendously less invasive and had a very good effect,” Babcock says. “Over three to six months, the body adds a layer or tissue over the device and it becomes part of the heart.”

Closing The Door On Blood Clots

Dr. Babcock also uses the St. Jude Amplatzer Septal Occluder to treat patent foramen ovale, or PFO. With PFO, a pressure release valve in the heart, which forms in utero and normally closes after birth, remains an open flap. As with ASD, the opening could allow a blood clot to travel from the right side of the heart to the left side, which brings blood to the rest of the body and the brain. The clot could then cause a stroke.